Miller’s Law: Designing for the Human Mind’s Memory Limit

Introduction

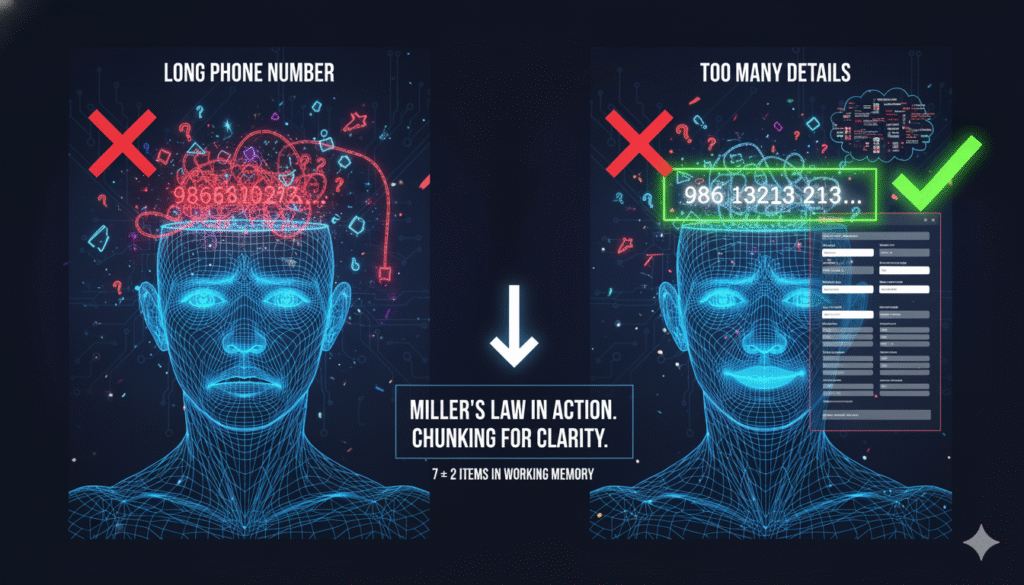

Ever tried remembering a long phone number and failed halfway?

Or got lost in a form asking for too many details at once?

That’s Miller’s Law in action.

Proposed in 1956 by cognitive psychologist George A. Miller, the law states that:

“The average person can hold 7 (plus or minus 2) items in their working memory.”

In simple terms, our brains can only juggle five to nine pieces of information at a time.

Go beyond that — and confusion sets in.

Or got lost in a form asking for too many details at once?

That’s Miller’s Law in action.

Proposed in 1956 by cognitive psychologist George A. Miller, the law states that:

“The average person can hold 7 (plus or minus 2) items in their working memory.”

In simple terms, our brains can only juggle five to nine pieces of information at a time.

Go beyond that — and confusion sets in.

The Science Behind the “Magic Number 7”

In 1956, cognitive psychologist George A. Miller published a paper titled “The Magical Number Seven, Plus or Minus Two.”

His finding was groundbreaking:

“The average person can hold about 7 (plus or minus 2) items in their working memory.”

That means most people can actively process five to nine pieces of information at once — before confusion or forgetfulness takes over.

Miller called this limit our channel capacity — the point where adding one more item causes errors or misjudgments.

Think of it like a mental inbox. Once it’s full, every new message pushes an old one out.

His finding was groundbreaking:

“The average person can hold about 7 (plus or minus 2) items in their working memory.”

That means most people can actively process five to nine pieces of information at once — before confusion or forgetfulness takes over.

Miller called this limit our channel capacity — the point where adding one more item causes errors or misjudgments.

Think of it like a mental inbox. Once it’s full, every new message pushes an old one out.

Classic Examples of Miller’s Law in Everyday Life

1. Car Number Plates — Memory in Motion

Car plates like DL 8C AH 1234 or MH 12 DE 4567 are designed with chunking in mind.

Even in a split second, you can read, store, and recall the sequence.

Why? Because it’s organized into smaller, meaningful blocks — letters, digits, regional codes.

This pattern-based grouping makes information easier to recognize.

That’s why witnesses can remember a number plate during stressful moments — the structured format aligns perfectly with our cognitive limits.

Even in a split second, you can read, store, and recall the sequence.

Why? Because it’s organized into smaller, meaningful blocks — letters, digits, regional codes.

This pattern-based grouping makes information easier to recognize.

That’s why witnesses can remember a number plate during stressful moments — the structured format aligns perfectly with our cognitive limits.

2. Phone Numbers — From Chaos to Clarity

Try memorizing this: 9861313213

Now try this: 986 1313 213.

The second one feels effortless. That’s chunking at work again.

By splitting data into smaller, digestible parts, we help our brains stay within the 7±2 limit.

This is why nearly every country formats phone numbers in clusters — they’re not just easier to read, they’re easier to remember.

The second one feels effortless. That’s chunking at work again.

By splitting data into smaller, digestible parts, we help our brains stay within the 7±2 limit.

This is why nearly every country formats phone numbers in clusters — they’re not just easier to read, they’re easier to remember.

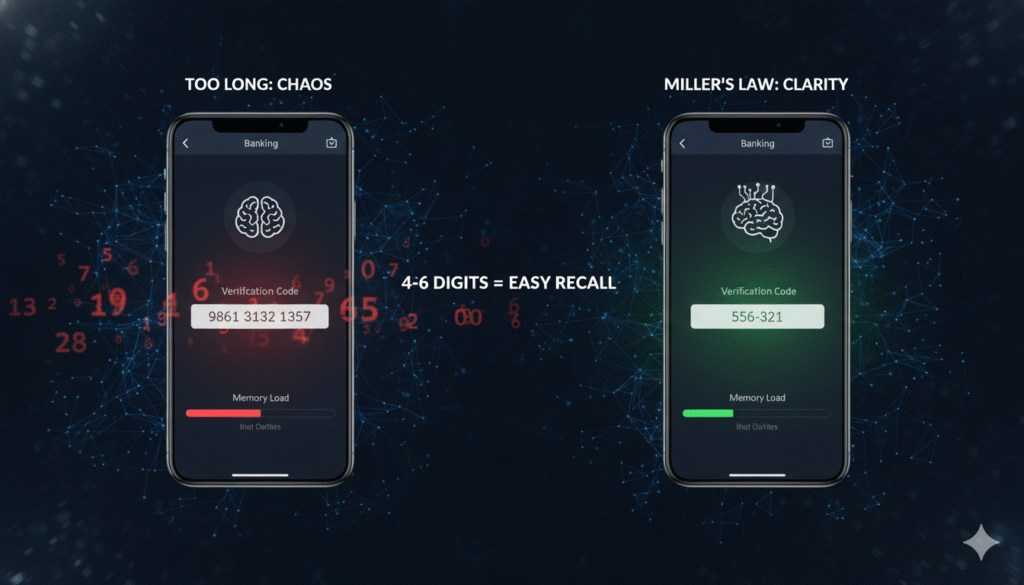

3. OTPs and Passwords — The Science of Recall

Most OTPs, PINs, or security codes are between 4 and 6 digits long.

It’s not random — it’s cognitive design.

Ask users to recall a 12-digit verification code, and accuracy plummets.

Keep it within Miller’s range, and people can type it from short-term memory instantly.

Every security interface, from banking apps to email logins, quietly respects Miller’s Law — ensuring the human mind never has to work harder than it should.

It’s not random — it’s cognitive design.

Ask users to recall a 12-digit verification code, and accuracy plummets.

Keep it within Miller’s range, and people can type it from short-term memory instantly.

Every security interface, from banking apps to email logins, quietly respects Miller’s Law — ensuring the human mind never has to work harder than it should.

Why This Matters in UX Design

Designing digital experiences isn’t just about color and layout — it’s about working with the brain, not against it.

When users encounter too many options, choices, or data points, their working memory overloads.

The result? Confusion, frustration, and drop-offs.

Miller’s Law helps designers combat that by organizing information in manageable, memorable chunks — a principle that shapes everything from navigation to dashboards.

When users encounter too many options, choices, or data points, their working memory overloads.

The result? Confusion, frustration, and drop-offs.

Miller’s Law helps designers combat that by organizing information in manageable, memorable chunks — a principle that shapes everything from navigation to dashboards.

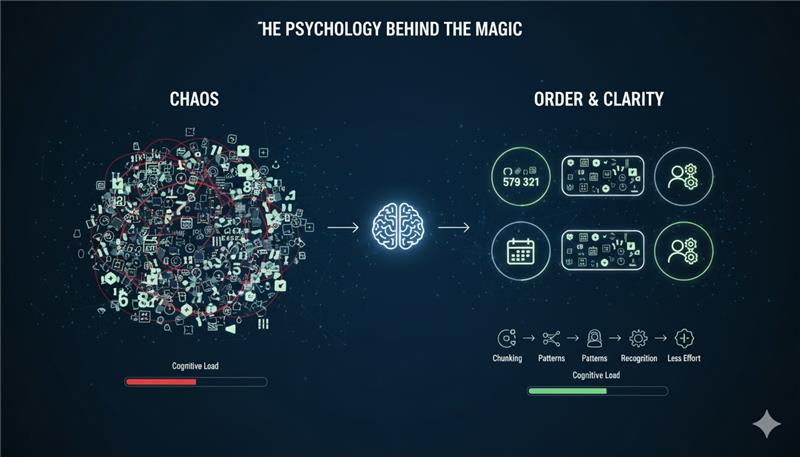

The Psychology Behind the Magic

Why does Miller’s Law work so well?

Because it mirrors the way we naturally seek order in chaos.

Because it mirrors the way we naturally seek order in chaos.

- Chunking transforms data into patterns.

- Patterns create recognition.

- Recognition reduces cognitive effort.

Key Takeaways

- The human brain can process 5–9 items at a time.

- Chunking helps users understand, recall, and act faster.

- Great design doesn’t fight memory — it flows with it.

- Simplify choices, group information, and users will thank you silently.

Conclusion: In a World of Noise, Stand Out Deliberately

Miller’s Law is more than a psychological principle — it’s a design philosophy.

It reminds us that clarity isn’t a visual trait; it’s a cognitive one.

By respecting how memory truly works, designers can craft interfaces that feel effortless, familiar, and human.

Because at the end of the day, the best designs don’t ask users to remember — they help them recognize.

It reminds us that clarity isn’t a visual trait; it’s a cognitive one.

By respecting how memory truly works, designers can craft interfaces that feel effortless, familiar, and human.

Because at the end of the day, the best designs don’t ask users to remember — they help them recognize.